Laini (Sylvia) Abernathy

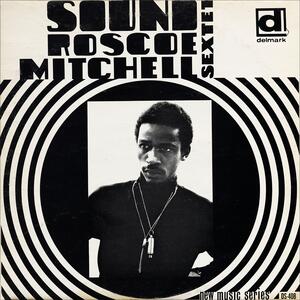

October 3, 2024Laini (Sylvia) Abernathy’s work for Delmark Records in the 1960s marks many firsts. Delmark Records, established in 1953 by Robert G. Koester in St. Louis and later relocating to Chicago in 1958, was the first continuously operating jazz and blues independent record label in the United States. In addition to releasing seminal works by numerous jazz and blues artists, Delmark Records notably supported musicians from Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. The first AACM record produced by Delmark was Roscoe Mitchell’s “Sound” (1966). Delmark also released two of the earliest Sun Ra albums, “Sun Song” (1967) and “Sound of Joy” (1968). Abernathy (d. 2010) is generally regarded as the first Black woman to design an album cover in what is largely considered to be a male-dominated industry.

Abernathy, along with her husband, photographer Fundi (Billy) Abernathy (1938-1917), was a key figure in Chicago’s Black Arts Movement (BAM) during the 1960s. Despite leaving behind a modest portfolio, her work resonates through a handful of album covers, a significant book design, and her design of the Wall of Respect mural in 1967, while studying at Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), a powerful symbol of Black heroes that stood until its unfortunate demolition in 1971 (24A-06).

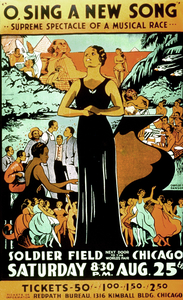

Her work reimagines Black identity in 1960s Chicago, echoing the artistic heritage of the Harlem Renaissance. Artists and designers like Aaron Douglas and Winold Reiss had earlier blended decorative elements with African sculptural motifs and expressed a deep cultural connection to the African continent within a modern context. The German immigrant Winold Reiss, primarily gave form to the aesthetic of the Harlem Renaissance with his portraiture of both prominent Black figures as well as common Harlem “types,” as he refers to this body of work. Dawson’s poster O Sing A New Song in the Chicago Design Archive Collection (19B-19) captures the way that Black identity was visualized during the interwar period, as universal and global, with roots extending to ancient Egypt, modern Africa, the American South, and urban metropolises in the North—their visual arts and musical expression carrying these histories into their forms. Jazz and blues were certainly an important part of the context of the Harlem Renaissance visual expressions, seen as fully modern and universal, but rooted in the very specific conditions and histories of the Black American, as J.A. Rogers puts it in his essay, “Jazz at Home,” published in Survey Graphic, Harlem Mecca of the Negro (March 1925).

Abernathy’s album covers for jazz saxophonist Roscoe Mitchell’s “Sound,” the photographic portrait of the musician, combined with strong black and white graphics echoes some of the tropes of graphic design of the Harlem Renaissance (24A-02). The typeface, like the earlier ones of 1920s Harlem, draws on decorative, Deco forms with thick-thin contrast that express dynamic movement, and even suggest musical beat, rhythm, and duration, as well as some of the spatial qualities of the music. Abernathy captures the hypnotic sounds on the album through the optical effects produced by black and white contrast, repetition of forms, and a central black circular element with Mitchell’s photo inserted (taken by Abernathy’s husband Fundi). He is wearing around his neck some of the instruments that he incorporates into the unique sounds on the album. The album was produced in the studio with other members of the AACM, including Lester Bowie (trumpet), Kalaparusha Maurice McIntire (tenor saxophone), Favors, Lester Lashley (trombone), and Alvin Fielder (drums). The album placed AACM squarely in the sphere of avant-garde or experimental jazz, which was emerging in 1960s Chicago, and that (like avant-garde composer John Cage’s work), incorporated unconventional sounds such as toys and bicycle horns.

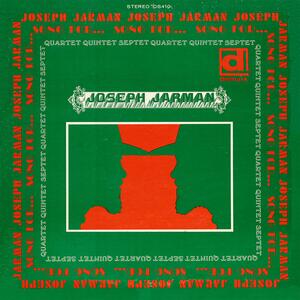

In another album cover, for the avant-garde musician Sun Ra (1914-1993), “Sun Song” (1966), Abernathy uses the entire surface to produce a gestural image of the sun in yellow, against a red ground (24A-04). In her 1967 album cover for Joseph Jarman’s album “Song For…,” Abernathy continues to play with historical typefaces and employs negative and positive contrast, in this case in the atonal colors of red and green (24A-01). The central photograph of the musician in “Sound” is replaced by two silhouetted profiles of Jarman wearing a hat, producing a gestalt image in which the figure and ground shift back and forth. In the album cover for Leon Sash’s “I Remember Newport” (1968), Abernathy inserts a photograph of the musician (by Lee Morgan) into a minimalist composition that references the American flag, at a moment during which the flag evoked complicated emotions both within and outside of the United States (24A-03).

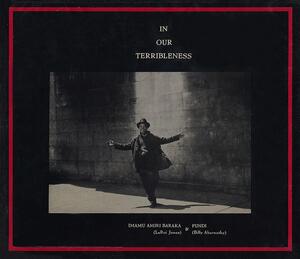

Beyond her album covers, Abernathy was involved as the graphic designer for the collaborative book In Our Terribleness, Some Elements and Meaning in Black Style, with poetry by Imamu Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) (1934-2014) and photographs by Abernathy’s husband, Fundi, published by Bobbs-Merrill press (Indianapolis) in 1970 (24A-05). As with some of her album covers, Abernathy uses frames to highlight the photographs and weave connection between the images and the words. Baraka establishes the context that inspired the project in the first few pages of the book: “There are mostly portraits here. Portraits of life. Of life being lived. Black People inspire us. Send life into us. Draw it in.” Some of Fundi’s photographs filled entire pages, in other cases, Abernathy centers them on the page and the text wraps both sides of the image. The non-static, always changing relationship between image and type refused formula. In a 1971 book review in The New York Times, the critic Ron Welburn saw this project as emblematic of “the new direction that [B]lack art is taking.” Portraiture was also employed during the Harlem Renaissance to elevate Black dignity and self-recognition. In Fundi’s photographs reproduced in the book, portraits are set in a context of street life and in an expression of a specific Black way of inhabiting life.

Abernathy’s legacy extends beyond design; she was a pivotal activist within the Black Arts Movement, contributing to community engagement and identity expression through her artistic endeavors. Her influence, epitomized by the Wall of Respect mural, continues to resonate in discussions of public art’s role in cultural expression and community empowerment. Again portraiture is used to express the accomplishments of Black musicians, politicians, athletes, writers, and community and religious leaders to inspire and transform Black consciousness within Chicago. The mural featured over 50 portraits across sections of a building at 43rd and Langley Avenue, painted against red, blue, green, black, and grey color blocks or segments of the wall. Today only photographs of the wall exist, as the building was destroyed by fire in 1971. In her brief but impactful career from approximately 1966 to 1968, Abernathy exemplified the transformative potential of design in articulating collective unity and identity within cultural movements.