Selling Design: 27 Chicago Designers 1936–1991

October 21, 2016

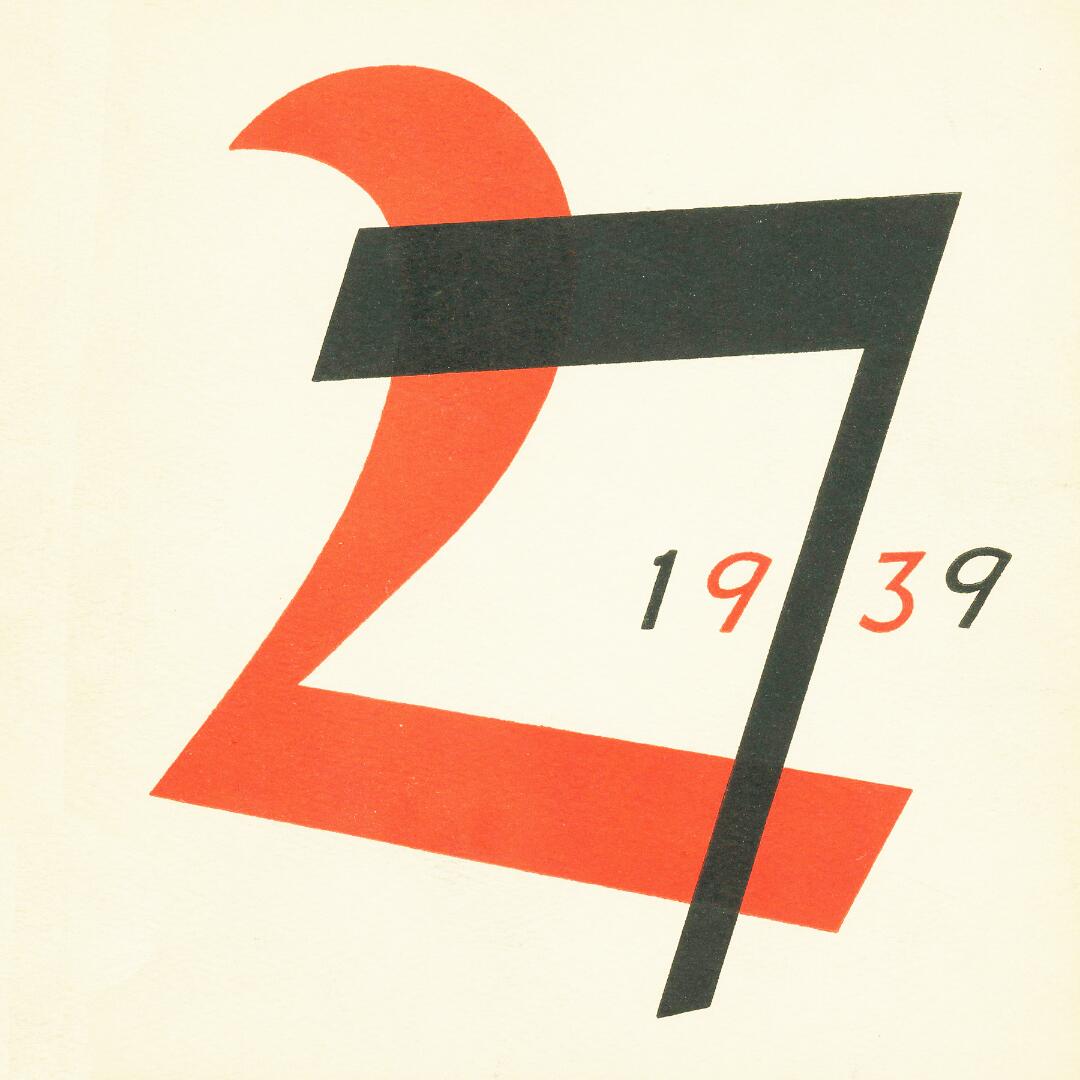

Volume 4, 1939

Introduction

Early in the twentieth century, several design organizations emerged in the United States to promote design’s relevance to business and public life, to establish design as a form of culture, and to produce professional standards and guidelines. The Society of Illustrators was formed in 1901 in New York. It was followed by The American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA), founded by Alfred Stieglitz, Wiliam Dwiggins, and Frederic Goudy in 1914, and the Art Director’s Club in 1920, founded by Earnest Elmo Calkins and Louis Pedlar. Seven years later, in 1927, the Society of Typographic Arts (STA) was organized in Chicago. All of these organizations facilitated the expanding role of the graphic arts—from a focus on printing and book publishing—to an embrace of commerce, advertising, and corporate communications.

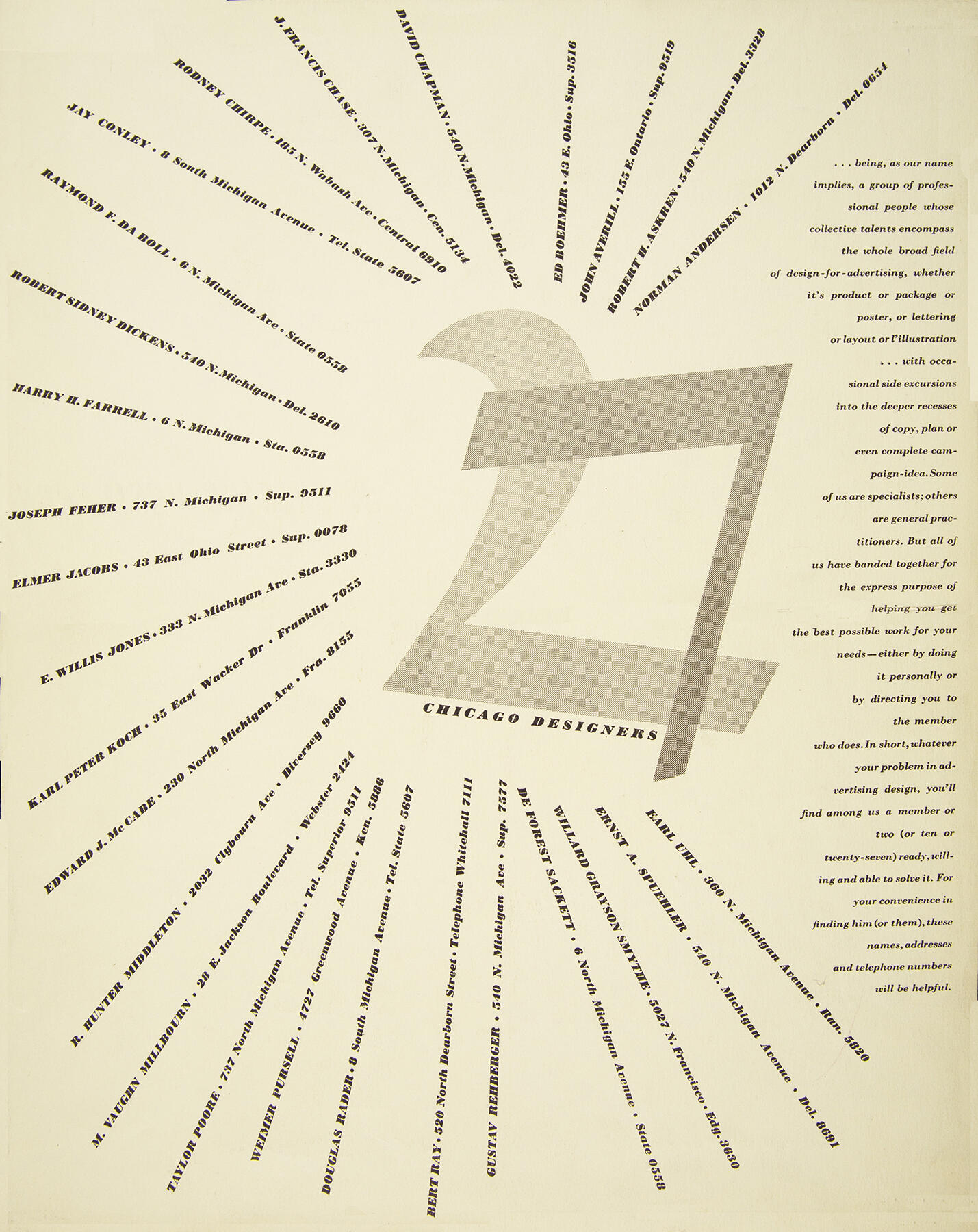

In 1936, during a period of reduced business investment and high unemployment, a unique design organization emerged in Chicago, called the 27 Chicago Designers. Composed of a group of 27 Chicago-based designers and illustrators under the leadership of illustrator John Averill, the group assembled their collective resources and talents to market their services to business organizations, largely through their annual publication, also titled 27 Chicago Designers. The publication, through the various contributors’ shifting professional titles and self-identifications, could be read as a quest for the meaning of design and for an overarching definition of the designer—critical inquires in the years of the group’s formation. The group promoted design as a good business investment to prospective clients and as an advanced form of communication with the public, embracing multiple practices.

For the annual publication, each member of the group independently designed and reproduced a four-page insert, consisting of a title page to identify themselves and three pages of recent design work. These inserts were collected and organized alphabetically by the designers’ last names, with a cover and introduction typically designed and written by the organization’s chairperson (a rotating position). The collection was bound and mailed to business executives and cultural leaders, to design and advertising firms, and to retail establishments in Chicago and other major U.S. cities. Client names were shared among the members of the group and the costs to produce and distribute the publication were divided among them. The designers also paid annual membership dues to cover any additional operating expenses.

Although the individual members worked autonomously in producing their own inserts, membership was strictly controlled. In keeping with the idea that the group would hold only 27 members (the original number of designer founders), a new designer was invited to join only when an existing member left. A new member, moreover, could only be considered for membership if he (and occasionally she) was recommended as an “outstanding” Chicago designer by an existing member and was then elected in by the group.

The organization—consisting of product and packaging designers, graphic artists and illustrators, calligraphers and typographers, art directors, and an architect—pivoted its identity around the word design. All of the members were designers—a term that was beginning to take on new meaning during the 1930s. 27 member DeForest Sackett described design as “that striking quality of efficient organization, coordination and simplification in a printed piece that characterizes all successful modern printing.”1

The group remained intact until 1991, another period of design transformation from the print to the digital age. Communication and access to clients was enhanced by the internet and the 27 Chicago Designers disbanded, not for lack of Chicago talent, but for loss of focus when one of its founding functions—to promote samples of their work to possible clients—no longer required print distribution.2. In its 55 years of existence, most of Chicago’s important graphic designers passed through its membership cycles. What was lost in the internet age was more than just the publication of an annual book—which we cherish today for its documentary and historical value—but the diminishment of a collective community of designers who shared and promoted each others’ work.

1 DeForest Sackett, STA Letter announcing annual lecture series, centered on “Design,” “…a new word that has assumed a new and vital significance…”. February 28, 1938.

2 Conversation, Jack Weiss and Joseph Essex, September, 2016.

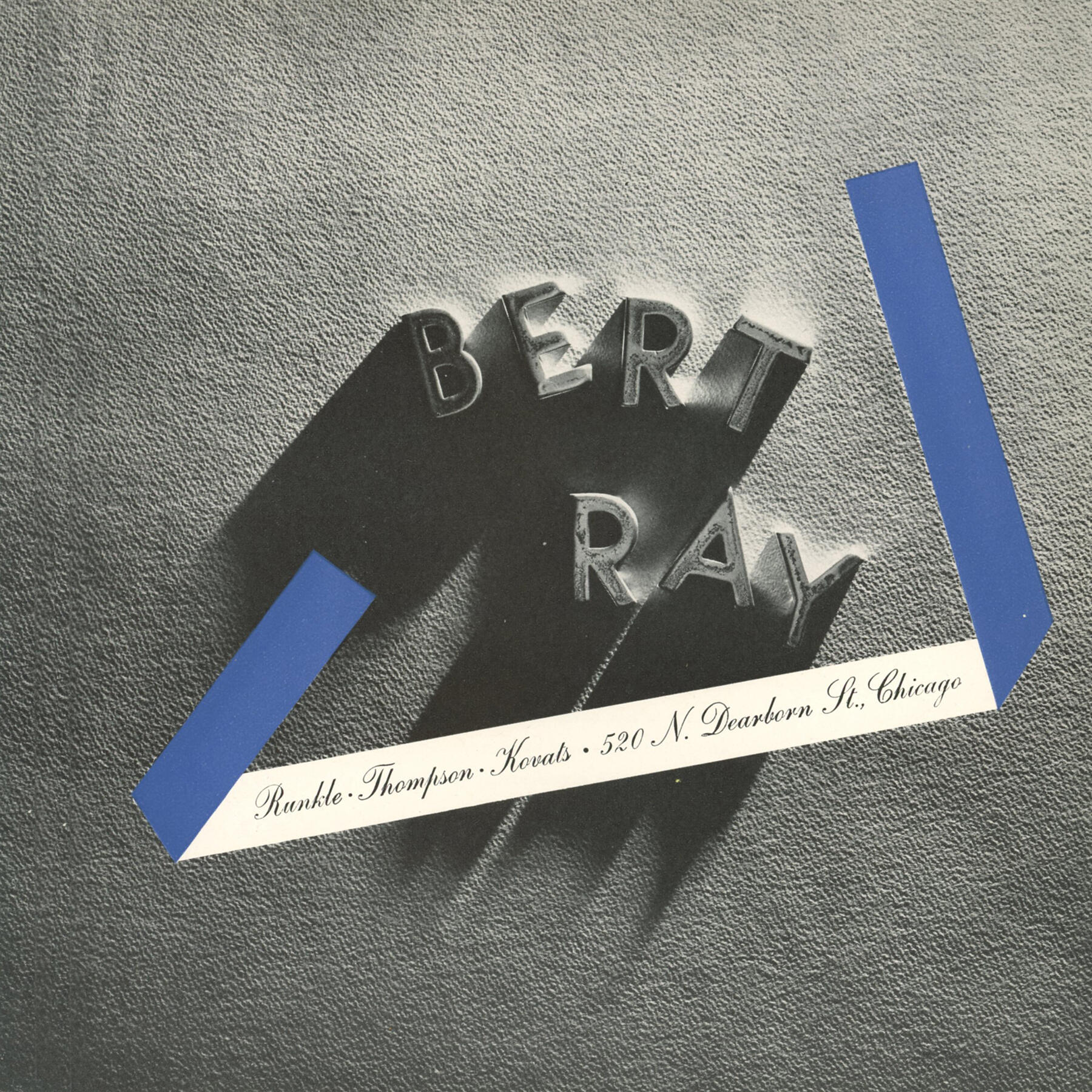

Bert Ray, 1945 (16E-147)

Typography & Calligraphy

Type design—both the invention of new typefaces and the refinement of lettering and calligraphy—was recognized by the 1930s as a key aspect of commercial design. Type on advertising pages, packages and corporate documents was employed not merely to produce a message, but to be integrated with illustration, photography, and other design elements to create a unified page and express meaning through formal integration.

Some of the 27 Chicago Designers founding members were letterers, calligraphers, and type designers—Oz Cooper, R.H. Middleton, Bert Ray, Frank Riley, Ray DaBoll and Joseph Carter. They understood that their work was to produce and select specialized letterforms to “sell the world’s goods,” in the words of Middleton. The proliferation of new typefaces was directly related to the expanding role of the letter within modern commerce and advertising.

The development of modern sans serif type was a frequent topic of conversation and concern for members of the 27 Chicago Designers. What marks the designers and founding members of the Chicago 27 Designers as unique in modern design history is their critical approach to both avant-garde typefaces, as promoted by European figures such as Jan Tschichold, Herbert Bayer, and László Moholy-Nagy, and to stylish trends associated with Art Deco.

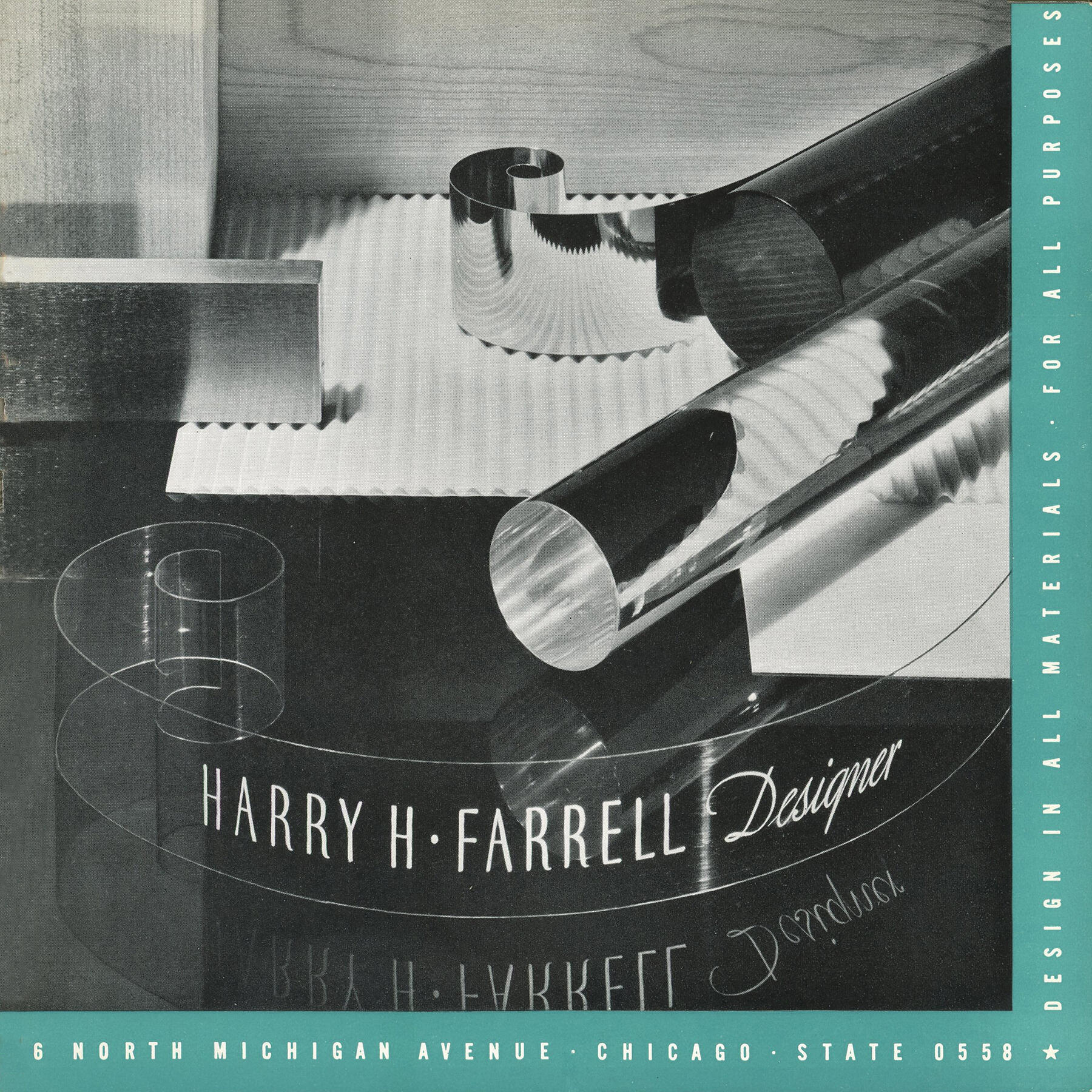

Henry Farrell, 1939 (16E-56)

Product, Packaging & 3-D

Founding and early 27 Chicago Design members Harry Farrell, Douglas Rader, Sidney Dickens, DeForest Sackett, Bert Ray, Ernst Spuehler, and Rodney Chirpe designed new packaging for many Chicago-based companies’ product lines. These companies included Abbott Laboratories, Walgreens Drugs, the Koller Brewing Company, Container Corporation of America, Sears, Roebuck & Co., Wrisley Soap Company, American Oil Company, Tested Papers of America, Inc., Parker Pens, U.S. Gypsum Company and Mills Novelty Company.

Product designers, including Dave Chapman and Everett Eckland, were also active 27 Designers. Eckland utilized the so-called “skyscraper style” to cloak machines such as golf ball and cigarette dispensers and radios in the most up-to-date and modern forms. These designers were perhaps more aware than illustrators and graphic designers of the importance of collaboration and integration among commercial artists. They composed three-dimensional advertisements utilizing the various elements of graphic design and experimented with modern materials in the pursuit of new packaging solutions and product possibilities.

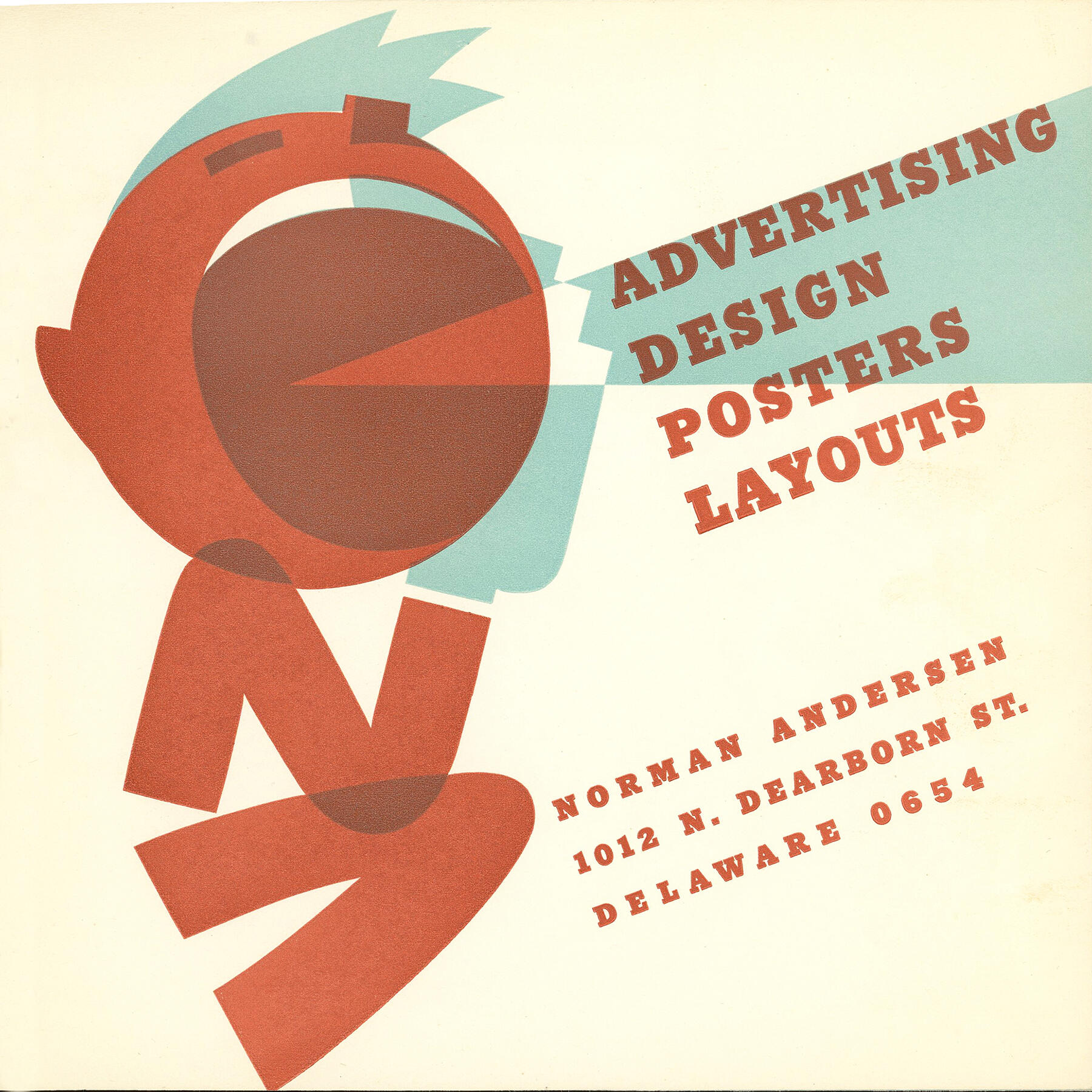

Norman Andersen, 1938 (16E-04)

Advertising Illustration & Photography

The 27 Chicago Designers’ efforts involved bringing commercial illustration and advertising (art direction) together with printing and typography under the same broad category of Design. During the 1920s and early 1930s, advertising and commercial illustration were widely considered to be separate intellectually and practically from the printing design arts (associated with books and type). The members of the 27 Designers promoted all of these fields as design practices, stressing the interconnections of type, illustration, layout, packaging and display, printing, and product design in a commercial context.

As photography played an increasingly important role in commercial graphics, illustrators still felt they had an important function through the expression of humor, exaggeration, and the employment of avant-garde or modernist composition and form. Illustrators staked out their own unique place within the field of commercial image making. Some of the representations are problematic as they employed stereotyped figures—especially of African Americans. The illustrations from the early years of the 27 Designers’ organization also reflected the interest in cubism, abstraction, and African art that was influencing European artists and designers during the first half of the twentieth century. Although some illustrators’ styles remained fairly consistent over time—including those of John Averill and Elmer Jacobs—other illustrators changed their style to reflect broader trends in modern art and graphic design.

R. Hunter Middleton, circa 1940

Collaboration

Collaboration was a cornerstone of the 27 Chicago Designers. Instead of viewing each other as competitors in a competitive economic environment, the designers believed that through showing their work together—in a single annual publication—they could enhance their professional profiles, gain new clients, and promote themselves more broadly. The members respected one another’s work, recruited each other for inclusion into the group, worked together on client accounts and assignments, shared studio space, and even formed design partnerships or practices.

The collaborative model established by the 27 Chicago Designers was emulated in splinter organizations, such as The Nine Illustrators, and in playful shared projects, such as Mother Goose. Above all, this model established the importance of integration—that art, illustration, type, exhibition, packaging, product design and architecture—were all aspects of design and all enhanced one another in successful communication.

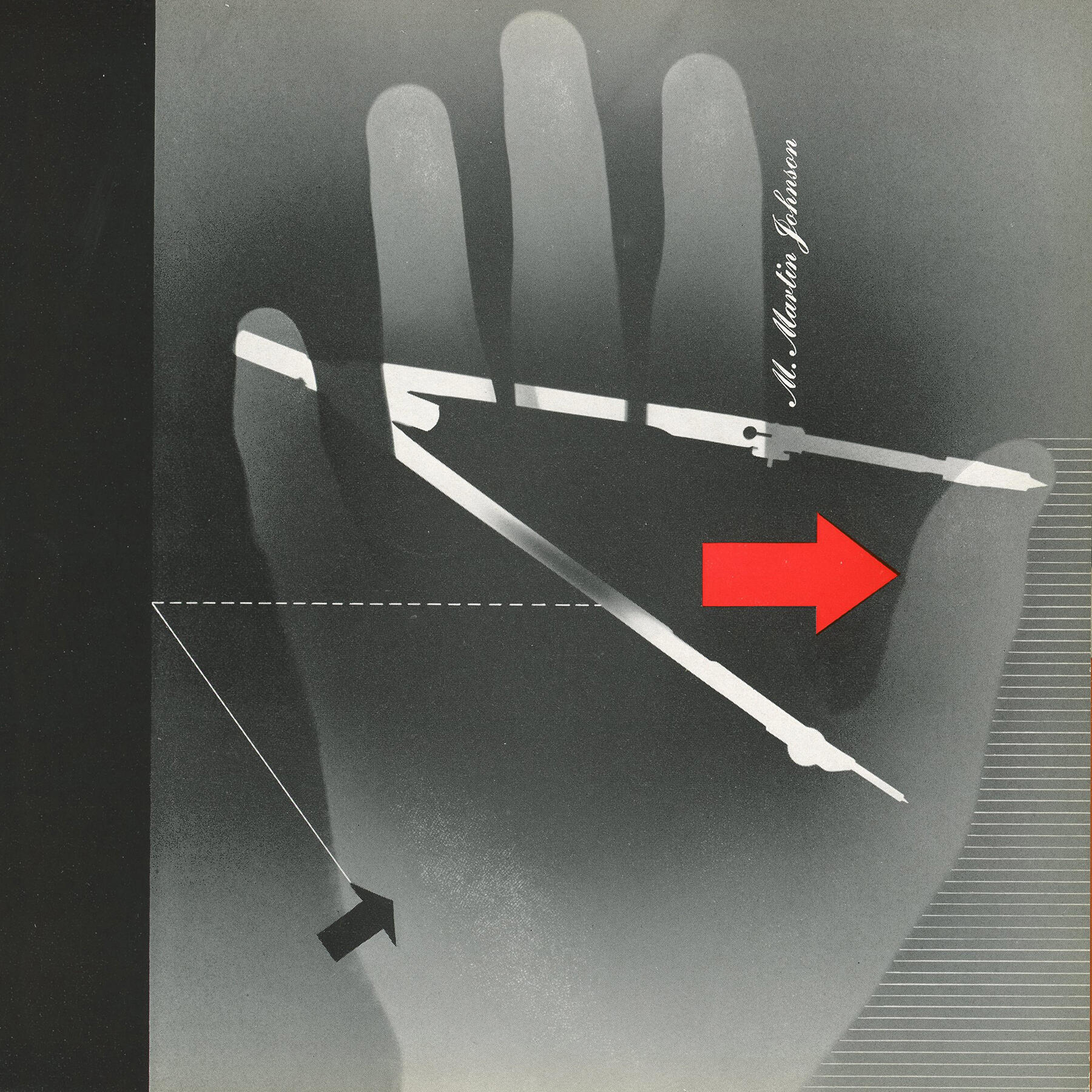

M. Martin Johnson, 1939 (1B-55)

Influence of the New Bauhaus

Just as the 27 Chicago Designers were organizing in the mid-1930s, the Association of Arts and Industries was making plans to set up an American Bauhaus school in Chicago. Although the school, first called the “New Bauhaus” under the direction of László Moholy-Nagy did not represent the first exposure of Chicago designers to modern and avant-grade design, it had a structural and long-lasting impact on Chicago designers, including members of the 27 Designers. Moholy and his associate from Europe, György Kepes, taught courses at the school on advertising and design. Faithful to the principles of the German Bauhaus model of art and design education, Kepes encouraged his students to return to the basics: form, color and composition. He introduced them to experimental photography, and the perceptual and psychological aspects of layout, texture, and scale.

27 Designers Joseph Feher, Clifford Eitel, Morton Goldsholl, M. Martin Johnson, Taylor Poore, and R. Hunter Middleton had their work included in Language of Vision, Kepes’s influential book on graphic design education, written and published in Chicago. This new design approach had a strong impact on Chicago designers. It offered a new attitude to graphic illustration and type, opened up experiments with new materials, encouraged a playful point of view towards composition, while promoting the avant-garde language of abstraction, dynamic page layout, and use of the basic shapes of the Bauhaus—witnessed in 27 Chicago Designers contributions by Everett Eckland, Harry Farrell, Egbert Jacobson, and R. Hunter Middleton.

Egbert Jacobson, 1937 (16E-79)

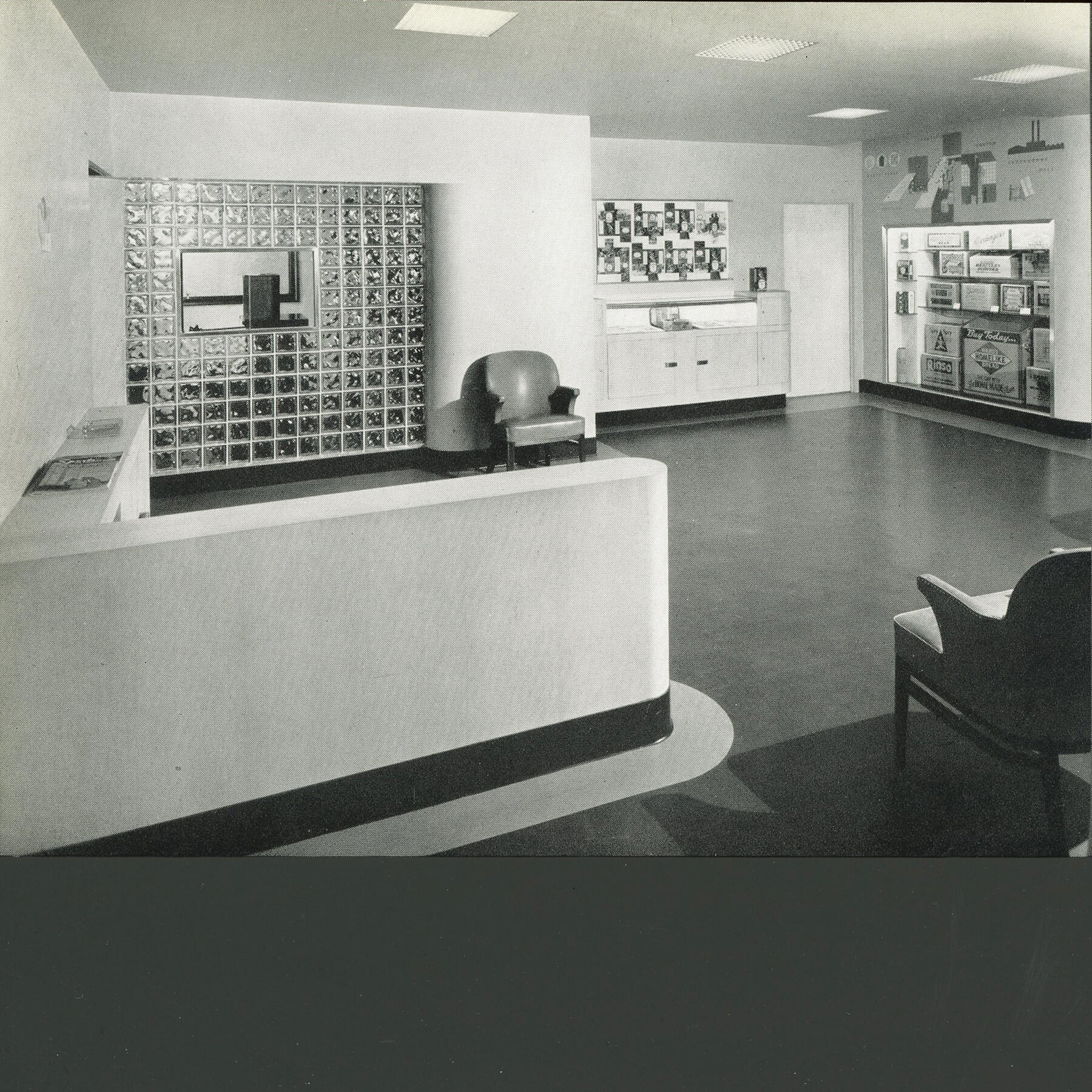

Corporate Design

The 27 Chicago Designers provided support for many Midwestern clients, working primarily as consulting art directors and designers. In 1936, 27 Designers founder, Egbert Jacobson was hired as an internal director of the newly formed design department at Chicago-based Container Corporation of America. In this position, Jacobson oversaw advertising campaigns and orchestrated the entire visual unification program, designing a logo, redesigning trucks, factories and offices for the company. Towards the middle of the century, other companies increasingly followed this development: hiring designers to develop designs that could sell not merely products, but corporate images and messages as well.

Acknowledgments

This essay was published on the occasion of the exhibition, Selling Design: 27 Chicago Designers, 1936-1991. The exhibition celebrates the 80th anniversary of the founding of the 27 Chicago Designers. Focusing on the founders, the exhibition charts the development of a collaborative approach to design, the incorporation of modernist and experimental materials and practices into commercial design culture, and the promotion of Chicago as a center for progressive design and advertising.

Curated by Lara Allison and Jack Weiss

Lara Allison, Ph.D., teaches art and design history at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Jack Weiss, past president and fellow of the Society of Typographic Arts, is director emeritus of the Chicago Design Archive and was a member of the 27 Chicago Designers from 1977 to 1991.

Concept by Jack Weiss

Exhibition by Lara Allison, Ron Kovach and Jack Weiss

Catalog design by Steve Liska and Ciana Frenze, printing donated by Blanchette Press

Book design by Joseph Essex, printing donated by Blanchette Press

Videos by Erin Borreson, The 27 Chicago Designers, 2012; Christopher Blake, Homage to the 27, 2016; Jack Weiss, 27 Chicago Designers: Selling Design, 2016 and 27 Chicago Designers: Current Work, 2016

Special thanks to Mary Case, Peggy Glowacki, Dan Harper, Valerie Harris, Linda Naru and Sonya Yaco at the University of Illinois at Chicago Library and to Paul Gehl and Alice Schreyer at the Newberry Library.

Support provided by the Chicago Design Archive, Bobbye Cochran, Joseph Michael Essex, John Greiner, A. Ma, Don Marvine, John Massey, Greg Samata, The Society of Typographic Arts, University of Illinois at Chicago, Jack Weiss and Lauren Whitney Photography.